By Dr Onoho’Omhen Ebhohimhen

Introduction

I am exceedingly glad for the rare privilege to anchor this conversation around Chief Tony Enahoro as An Icon of Leadership. I got an intimation of the work in early October 2023. The long notice gave me time to reflect. My initial impression was that of utter trepidation. Because the invitation to review the book was more of a thinly veiled demarche than a request. Then, I had second thoughts. In the end, I found that I was neither troubled by the manoeuvre of my colleagues in the Uromi People’s Movement nor afraid of the sort of intellectual rigour expected in discussing this feat of an account of the life and times of Chief Anthony Eronsele Enahoro. Although I recognized the enormous challenge inherent in the questions posed by the book, yet, I eagerly looked forward to its public appearance.

Since October 2023, when I accepted to undertake the task, I have been honoured by the Ojuromi of Uromi with Ojietemon and was invested with the traditional title of the King has the final word in Uromi on 16th December 2023. The President and members of the Uromi People’s Movement were there to support me. This assignment forms a part of my service to Uromi and our people as the Ojietemon. As a past President of the Movement, I also owe a cherished obligation to report for duty. Therefore, I have more than perfunctory reasons to be involved in the affairs of Uromi and the Movement and to perform this task.

In the engagement, I intend to offer a guide, cultivate potential readers, attempt to interrogate ingrained misperceptions and ultimately, throw a few gauntlets, here and there.

The book

This book is both subjective and objective. First, It represents the author’s reflection on a set of factual expositions of the life and work of his uncle. And second, it simultaneously presents recorded events and verifiable facts, which are open, in the public space but need to be lent topicality and pertinent analyses.

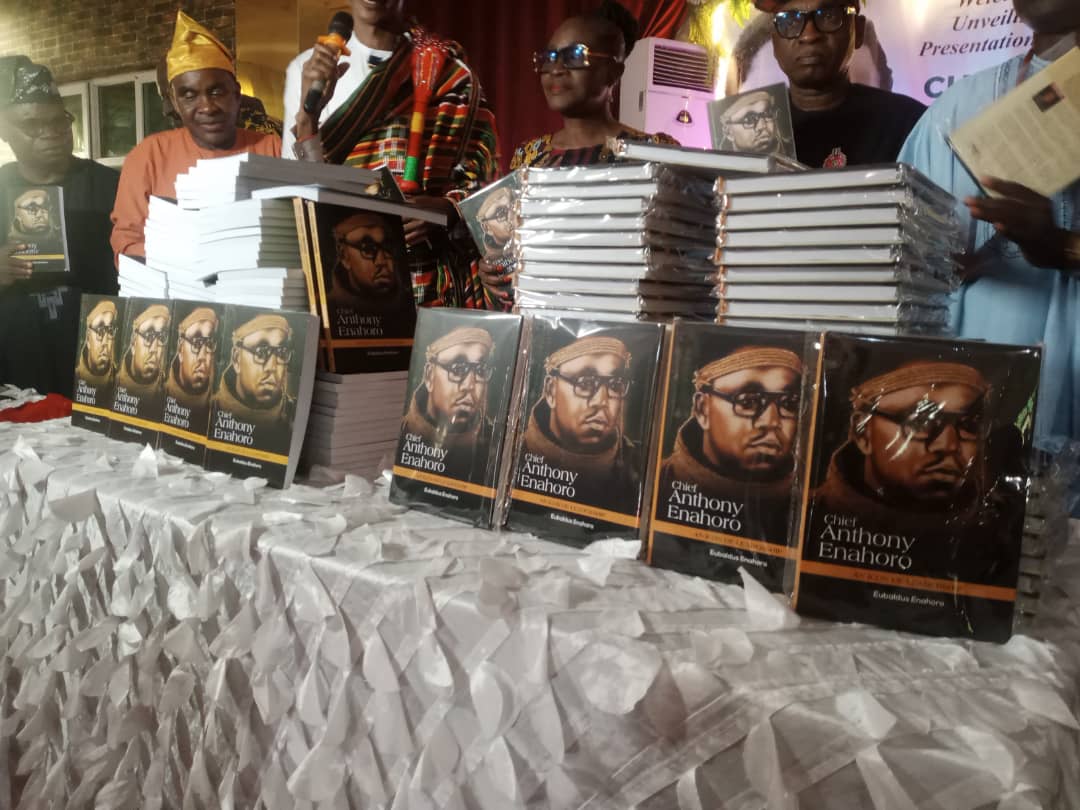

The book is over 200 pages long and was published by Mindex Publishers and the Uromi People’s Movement. The scope of the book seems limited. However, it contains major historical deeds and leverages contemporaneous actions, which are generously spread across several chapters. If we add the verso pages, preliminaries or front matter, end matter or epilogic representations, we may argue that the book is neatly divisible into twelve parts. We lack the generosity of time to deal with each chapter seriatim.

Each portion of the book tells a scintillating story of Chief Anthony Eronsele Enahoro, ranging from a profile of courageous struggle to an aesthetic portraiture of the man. There is an equally candid assessment of his anodyne work and the great feats he accomplished in public life.

I should add that the author appeared well-intentioned and adequately balanced to have argued a considerable proposition that Chief Anthony Enahoro nursed a deep passion for good governance. (I will concretely situate this assumption later). The author similarly regaled readers with some selected speeches, press interviews and reviews, including vintage photographs of Chief Anthony Enahoro at work and play, meetings and in his execution of public duties.

I am inclined to baulk to detail the individual arguments in the book. Instead, I will simply contextualise some of its profound issues. I thoroughly enjoyed reading the book and would like to review it in a contextual format. So, I will endeavour to shun laborious scholarly discussion and methodological turgidity. Before I venture to discuss the issues, let me offer some counsel – and I do so in absolute confidence. Readers of this book will gain more from the rich resources placed at our disposal if they distill the facts by themselves.

On the important discourse of the book, let us begin with the ontological contexts.

Leaders without ideology

Professor Emmanuel Ayantayo Ayandele of the University of Ibadan fame and pioneer Vice Chancellor of the University of Calabar, once rued some concerning incidences in our country’s history. Among others, he found that the early shapers of our national consciousness, as well as foremost fighters for autonomous governance, failed to independently conceptualise, represent or domesticate any of the great systematized body of thoughts known as ideologies. Ayandele as a classical scholar, blamed the colonial education system. He reasoned that the non-Western educated natives effortlessly disposed of the “colo-mentality” of their elite counterparts as “decivilised and denatured.” To be precise, the natives thought members of the Western-educated Nigerian elite were shallow and lacking in operational magnitude in society. Ayandele located the conundrum of the contestation between the modern elite and their traditional counterparts within the ebb and flow of the tide of the educated elite’s engagement with colonialism and the intramural struggle for leadership. Therefore, he was not surprised by the succeeding vacuity of post-independent governance.

Despite the critical weaknesses and fundamental drawbacks of those Ayandele characterized as deluded hybrids and collaborators – all pretenders to modernity. However, many of the educated elite overthrew and surpassed the natural rulers. The modern elite then rose to the apex of the national leadership structure. Some of the educated elite consequently dominated the loop of Nigeria’s power configurations. However, their political governance style was vacuous and naturally ended up as sterile. All this predictably, soiled a stainless banner.

Chief Anthony Eronsele Enahoro was a shining star in Nigeria’s independence struggle. Hence, we need to partly contextualise Ayandele’s arguments around him. It suffices to quote Professor Ayandele verbatim,

The appalling result of the benumbing colonial educational system in which the educated elite had been brought up is that they not only seem incapable of formulating ideologies, they seem as well unable to understand and adapt to the Nigerian situation, world-conquering ideologies which are being turned to advantage in other parts of Africa. One cannot talk of a system of thought to be dubbed Azikiweism, Awolowoism, Belloism or Enahoroism in the way one can talk of Nkrumahism.

By inference, Professor Ayandele did not seriously take account of recent historical specificities in the period captured in his pithy but agonizing remarks. At least, some acolytes of Dr Nnamdi Azikiwe had attempted to formulate a conceptual aggregation known as Zikism. This acronym is quite familiar in the particular historical iterations of the NCNC and in the nationalist struggle for political independence, generally.

In the post-independence period, especially around the 1970s, Chief Obafemi Awolowo published tomes of books on an avowed philosophy of public governance; he tackled the problematic of how to procure substantive development and made definitive suggestions for a good constitution for Nigeria, respectively. Serially, some followers of Chief Awolowo endeavoured to construct an ideology out of the books and political ideas to project a platform for the world to engage the Sage. Especially, Akin Omoboriowo, Ebenezer Babatope and a Catholic priest propounded hypotheses to further develop, refine, contextualise and altogether consolidate Chief Awolowo’s vision. The thoughts of Awolowo, construed against the backdrop of ideas of public governance and autonomous development were presented as quintessential. Thus, the various authors and followers labelled and articulated the summum bonum of Awolowo. Thus, Awoism is a political ideology of Nigeria’s development distilled from the thoughts of Chief Obafemi Awolowo.

Correspondingly, the leadership style, accumulated traditional and administrative qualitative outcomes; and the totality of the Sir Ahmadu Bello persona were resurrected from the desuetude sadly imposed by the 16th January 1966 wahala. Ahmadu Bello was ascriptive and customarily shaped. However, his perspectives have been concurrently moulded to resonate in the body politic of our country. The relevant works on Sir Ahmadu Bello whether produced by commissioned indigenous authors or sponsored expatriate scholars are plentiful. The related accounts unceasingly reveal his hopes, fears and concerns for Northern Nigeria. Every bit of the life and times of Sir Ahmadu Bello was carefully fashioned and related to a particular notion of the development of Nigeria. Consequently, Ahmadu Bello’s life and work were synthesized to appeal to a general readership.

Even Ahmadu Bello’s controversial exertions have been accorded favourable accounting. For example, his policy aimed at erecting artificial frontiers against the plausible assault on Northern Nigeria by some aggressive southern nationals, chiefly jobs and opportunity-seeking, relatively tactless countrymen has received healthily sympathetic explanations. Overall, it is safe to state that the political substance of Sir Ahmadu Bello is condensed in the prototypical abstraction of Gamji. So, Ahmadu Bello’s life and ideas were elevated to a creed.

Anyway, what Professor Ayandele had in mind may be slightly different from the posteriori political jiggery-pokery to explain a not altogether stellar past or impose an attractive recollection of prickly facts. Ayandele appeared concerned by the penchant to copy and graft poorly digested ideations and frowned at those leaders who appropriated lackadaisy as a badge of honour. He emphatically criticised the absence of the slightest effort at the adaptation of the great world-changing ideas to our concrete situation. The failure or absence of rigour to enrich one’s environment or transform the surrounding milieu understandably perturbed Ayandele. Unfortunately, the censured past has remained and prospects of change are becoming difficult; this is worrisome. Well, this is not the right place and time to deal with the many rarefied implications of Ayandele’s arguments. What is important is to return to our first principles.

My immediate concern is that it goes without saying that we may identify a contemporaneous void in the historicity of scholarly arguments about constructing an ideology for Nigeria. Significantly, the profound thoughts of Chief Anthony Enahoro had hitherto, suffered seeming neglect. Yet, Chief Enahoro was an exemplary new Nigerian who transcended restrictive cultural roots. He nursed deep insights into Nigeria’s problems and his creative imaginaries trumped the binary of conceptual contradictions. Chief Anthony Enahoro had excellent projections about the national growth and purpose of Nigeria. Every time Chief Anthony Enahoro intervened in the national debate, he brilliantly espoused efficacious remedies to any incapacitating disorder.

Fortunately for us, Chief Enahoro recorded some of his thoughts and work in writings, preserved them in many statements and published books and articles. As a result, the requisite materiel existed, abounding in plenitude that only efforts and inspiration had been lacking in the construction of Enahoroism. That such a serious matter about Chief Enahoro’s impact had been left in abeyance was underserving. This may be due to a singular remission in the Nigerian project. In other words, there is a fundamental contradiction inherent in our national system. The reigning order seems to valorise idlers. The national situational approach distressingly represents as socially disadvantaged the best of our citizens, philosophers and good-hearted political iconoclasts, the salt of the nation. However profound or great, since these citizens did not accumulate filthy lucre, Nigeria’s best and most useful are severely avoided or worse, utterly marginalised.

Put differently, our country’s profound thinkers, able wise men and women without the paraphernalia of power and free of plenteous sleaze, a deep purse and sundry avenues to dispense political patronage, are discarded. Even, some of their expected zealots boldly refrain from drinking from the deep well of their lives. Worse, their followers are unable to derive valued experience from their work. In this connection, Chief Enahoro was not alone. After all, one can also take solace that the great philosophers and universal historical figures were not simultaneously power merchants and patronage dispensers.

Enahoroism

Happily, the book under review also surveyed the prophecy and philosophy of Chief Anthony Enahoro. We can restructure his books, articles and writings generally; his cutting-edge interventions in national debates and magnify them through ideological prisms. Logically, the ideas in the book represent some of the substance needed for Enahoroism! Besides, some parts of the book featured the chronicles of Chief Anthony Enahoro’s selfless combat to cauterize leadership failure in Nigeria. That would be an interesting theoretical point as it represents a moral magnitude. This context concretely ensconces him within the paradigmatic representation of a conscious member of the elite. Hence, Chief Anthony Enahoro was not only preternaturally more perceptive but also, self-aware and keenly interested in elite preservation. He understood enough, the fragility of the loop surrounding the Nigerian elite that he strove hard to prevent the gory prospects of state failure.

Nonetheless, to properly situate Enahoroism, we will return to the point of whether Nigeria was worth the sacrifice, loss of freedom and harassment which Chief Anthony Enahoro endured during his inexorable struggle for independence and its aftermath. We may graft the successive years of his clamour for good quality governmentality and public service delivery into the debate. In chapters and pages of the book, Chief Enahoro was confronted with the enigma and was pointedly asked troubling questions about our country. He was categorical that the problem of Nigeria is monumental. Therefore, Enahoroism would be about the peaceful development of Nigeria by the harmonisation of the endogenous attributes of our country to engage the zeitgeist of African humanity.

Nigeria needs an Enahoro

The publication of this book serves an overarching and useful national purpose. One is not afraid to say that if this book were not published at this time, it would certainly have been reasonable to invent it. At the critical conjunctures in our country, too often, we hit a fork in the road and instead of thinking of the most sensible path to chart, we embark on the accursed Sisyphean rolling of a boulder uphill. In the existing context, the unconventional wisdom, creativity and guarding hands of Chief Anthony Enahoro are sorely needed to meander our country out of the dark woods. I will endeavour to return to this subject later as well.

Enahoro as a new NigerianIt was the same Professor Ayandele who excused Chief Anthony Enahoro from colonial collaborators who were comfortable as British subjects. In his view, Chief Enahoro was also not among the wind sowers who imagined they were national figures. Instead, Chief Enahoro was located firmly among the truly new Nigerians. However, I am not sure if Chief Enahoro agreed with this trajectory of analysis or characterisation. Of course, he was not the sort of person to be identified with others who subverted the ideal ethos of “inherent cohesion… but clearly aligning against the dysfunctional forces” in Nigeria. This could partly explain Chief Enahoro’s commitment to keeping Nigeria united. He was conscious of his roots but also, thought that Nigeria was a work in progress worth all the efforts. He did not doubt that passionate and modernizing citizenship would clash with atavism or that societal stasis and archaic perception of Nigeria would need to be confronted by the countervailing forces of the inevitability of progress. Nevertheless, like a piece of wet clay, the book is definitive that Chief Enahoro held that Nigeria can endure continuous moulding and refinement.

Perhaps, readers will recall and the book attests that Chief Enahoro himself argued in dissimilar contexts of power accretion or better still, power investiture in our country. For Chief Enahoro, a major incongruity of Nigeria was that those who laboured for, and made sacrifices that every freedom-loving Nigerian was behind bars, ended up with the short end of the stick. Young Nigerians like him had plodded on and scaled every conceivable obstacle to obtain independence for our country but did not have the opportunity to lead or govern an independent Nigeria. This untoward turn of events largely accounts for the failure of substantive governance.

Although every one of the exogenously superimposed official leaders may be assumed to be committed to building a nation, it was inevitably a Herculean task for them, tantamount to untying the Gordian knot. The consecrated official national leaders were either novices or latter-day converts to the independence struggle. And so, it was unsurprising that our national history is riven with post-independence leaders thrown up by a quixotic system. Despite being entrusted with the official levers of power, their lack of grit, amplitude of vision and tolerance of robust political debate did us a bad blow. Accordingly, the official leaders unable to meld the multiplicity of outlooks, varied social and psychological structures and collate disparate economic visions and cultural particularities could not procure substantive development for Nigeria.

To be precise, one is not baiting history to observe that some pre-independence Nigerians mutually nursed divergent antipathies and in this post-independence era, many still hold completely conflicting ideas about what Nigeria represents, including its relevance to her citizens. The sketchy definition and cavalier engagement with Nigeria echo in the subsisting absence of a commonality of national consciousness, an acceptance of what constitutes essential Nigeria. Significantly, the visionless quandary bequeathed at independence has led many otherwise serious-minded citizens to question if Nigeria was worth the fig, after all. This is a valid point for further enquiry at another level. Still, this book is full of examples that Chief Enahoro held strong views on the purpose of Nigeria. He was neither induced by any scaremongering to keep his peace nor did he regard old collegial relations as self-sufficient for him to live in a placid existence. Hopefully, we will situate the pertinent issues in the debate, presently.

Enahoro and good governance

To briefly highlight what good governance should epitomise, in the logic of Chief Enahoro, it is necessary to interrogate it conceptually if only to situate its clarification and overcome current blinkered perceptions. The common mistake that we make as Nigerians is to think that the leadership of governments is engaged in good governance if it provides social and economic services. These are simply needed opportunities for transformation. It is wrong to mischaracterise public duty but the error is understandable since our governments sparingly undertake physical development milestones.

The profile of service of Chief Enahoro occupies a different flank of the concept of the good governance paradigm. He had national name recognition all right. It was derived from his journalistic work, mastery of parliamentary skills and general political exploits. But to his Esan natives, Chief Enahoro exerted an everlasting impact that was considered the fulcrum of service to the people. Indeed, Chief Anthony Enahoro significantly transformed the bucolic landscape of his constituency. His representation of his people in the Western Regional legislature and subsequently, as Regional Minister, resulted in the development and extension of a pipe-borne water system to Esan. A General Hospital, telecommunication services and a post office were also built and commissioned. The road traversing most of the northern Ishan district was constructed and macadamized. It was also during Chief Anthony Enahoro’s chairmanship of the Ishan Divisional Council that a secondary school, aptly, named Ishan Grammar School, was conceptualised and built by the Ishan Divisional Council.

Besides the extension of high education opportunities to young men and women, Chief Enahoro’s presence in government was also instrumental in combating childhood infections and adult diseases. The Western Regional government adopted measures which effectively curtailed infant and adolescent mortality and saved otherwise able-bodied adults from crippling ailments. The supply of clean water resulted in the avoidance of harvesting rainwater outflows stored in community ponds. Mass infant vaccination ensured checking epidemic outbreaks. The prompt treatment of sick children ensured the rapid decline of infant mortality.

Chief Enahoro’s impact was also visible in the eradication of yaws and guinea worms. The endemic water-borne diseases had for centuries afflicted the Esan people. The debilitating effects of the diseases are copiously related in Esan orature, expounded upon in health talks and recounted in the general historical experience of the Esan people.

Thus, Chief Anthony Enahoro’s name is engraved in the heart of the Esan people and woven into the folklore for his outstanding facilitation as a parliamentarian and Minister in the Western Regional government.

In political science and social theory generally, a legislator has three functions: these are law-making, parliamentary oversight of public-funded projects and representation. In consequence, the annals of service of Chief Anthony Enahoro, which we have summarised, fall directly under the rubric of effective representation. Of course, this is not to suggest that we should ignore the enduring philosophical debate about good governance.

Good governance through the ages

The question of good governance is deep in antiquity and enjoyed considerable interrogation as far back as the era of Aristotle. One could draw a comparison with historical instances where good governance was considered an antidote to or means of preventing revolutions. In this context, Aristotle construed revolutions to include any major or minor change in the constitution such as a change in monarchy or oligarchy. He also inferred that a revolution is a change in the ruling power even though it may not lead to a fundamental rupture in the government or the overthrow of the constitution. In the end, Aristotle proposed the imperative to promote the laudatory goals of good governance; he called this a good constitution as opposed to a perverted one so as to stave off revolutions.

Emphatically, the modern postulation of good governance is a different kettle of fish. Even conceptually, good governance in the modern context embraces processes applied by public institutions to conduct public affairs and manage public resources that promote the observance of the rule of law and the realization of human rights, embracing civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights. The United Nations listed eight major characteristics of good governance. The UN-ESCAP report underscores the substratum of participatory, consensus-oriented, accountable, transparent, responsive, effective, efficient, equitable and inclusive public management and that it follows the rule of law. Therefore, good governance ensures that corruption is minimized, the views of minorities are taken into account and the voices of the most vulnerable in society are heard in decision-making. It also entails a responsive approach to the present and future needs of society.

Governing as self-glorification

How many governments in Nigeria today care a hoot about the participation of the people in governance or consensus-oriented and inclusive public management consistent with the rule of law? And how many constituency projects in the last twenty years have exerted the undying impact of the sort that Chief Enahoro’s representation at the Western House of Assembly between 1954 and 1959 brought to his constituents in less than six years?

There has been an impulsive national attitudinal relationship not with good governance qua process but with self-glorification as evinced in the ego trip of our leaders. Especially since 1999, sloganeering without discernible due process has dominated the landscape of governance. It has disconcertingly become a national habit to misrepresent high falutin fads, revelling not in the substantiation of appropriating duties of governments for the welfare of the citizens. It is troubling that Nigerians tend to conflate the principles and observance of rules of public conduct with the substance of political leadership. Thus, statecraft has become pointless as the needed rapid economic development is consigned into indeterminate abeyance and conferment of welfare on the people left to uncertain foreign-crafted parameters and maybe, unrealisable imagination.

It seems to be the case that due to our misinterpretation of good governance, we do not mind if governments indulge in flagrant abuse, operate without respect for rules or trample upon processes. Insofar as the government officials appeal to us and we occupy a corner in the gravy train, we celebrate the leaders of the governments. Even when executing their anodyne responsibilities, our public office holders and political leaders want to be considered social celebrities and songs of praise waxed in their honour. This is despite that the institution of government was established to deliver unexcludable public goods. So much for good governance.

If Chief Anthony Enahoro were with us today, he would relentlessly urge that we too, should rescue good governance from the deep pit, clean and disinfect it of the despoilation in the current national muck and confusion. Therefore, Chief Enahoro represented an era with a cri de couer for substantive development. He could not have brooked poor governance outcomes. He rightly held that governments must not be categorised against the backdrop of ordinary governmentality or should development be measured against the least veritable indices.

Enahoro and unfinished works

We read in pages of the book about the three steps proposed to eternalise the appearance of the Enahoro phenomenon. The situation practically draws attention to the checklist of the tasks. Molara Wood suggested the tasks which were in consideration around 2007. The first was the revision of The Fugitive Offender: The Story of a Political Prisoner for publication in a new and expanded edition. Since the book was first published by Cassell in 1965, there has been an evident hiatus in the issues canvassed. And so, certain things need revision and elaboration, re-evaluation and perhaps, reconsideration. The second in the checklist was the publication of his selected speeches and writings, and the third was the completion of his Memoir.

On the first point, it was rightly held that many young Nigerians have not had the opportunity to read The Fugitive Offender. I, myself, read a borrowed copy in 1983 and dutifully returned it to its owner. I have practically forgotten most of its details, except the debatable Ikpotokin storyline. I should assume firstly, that the task of revising for reissue of The Fugitive Offender had received deserved attention. Chief Enahoro made so many notations on the book as he worked to update it. So far, the new edition of The Fugitive Offender is not obtainable in the bookshops and the original edition is practically exhausted at online bookstores.

Secondly, the compilation of some of his writings into a book form was completed by Chief Enahoro before his exit. The book was appropriately titled Liberate and Democratise Nigeria. It featured some seventy of his key speeches and was published by Macmillan Nigeria in 2010. It is a hefty tome of 534 pages. Although one cannot recollect if the book was formally presented, however, it is in full circulation and available on Google Books, Amazon and so on. It is plausible that Chief Enahoro may have had the mind for another collection of his speeches, statements and so on for yet another publication.

One does not know enough about the outcome of the third item, the Memoir. However, Sahara Reporters featured a story on 17th December 2010 that Chief Enahoro disclosed “some preliminary documents have been signed with Macmillian. According to the agreement, the actual Memoir will be preceded by a collection of some of the landmark political speeches given by him over the years.” We have already alluded to that preceding condition as having been done. Anyway, someone raised the subject of the Memoir with Ken Enahoro – God bless his soul. Ken reportedly remonstrated and acknowledged that his father indeed, left a huge task.

Altogether, Ken had an engaging attitude as he insisted that there existed a bountiful resource base. The treasure trove of documents could form enduring materials for research to tell credible stories, reconstruct Chief Anthony Enahoro’s life and continue his unfinished work. In other words, there is the real possibility to pursue the identified sources of knowledge, a storehouse of valuable contributions to history and clarification of confusion by following the path already charted by Chief Anthony Enahoro himself. This could include reviving the pact with Macmillan to perhaps, complete the partially conceptualised Memoir of Chief Anthony Enahoro.

The need for the Anthony Enahoro Foundation

I would like to seize this opportunity to throw a few gauntlets. Firstly, I urge research entities, academic institutions and scholarly organisations, the vast relations of Chief Anthony Enahoro, his acolytes and development scholars alike to work for the establishment of an Anthony Enahoro Foundation. There is a gulf in our knowledge of the Chief Enahoro phenomenon. What he meant, the kind of Nigeria he laboured for and what emerged deserve serious scholarly enquiry. We should move intentionally to fill the gaping hole.

It is equally significant that the leadership performativity of Nigeria is now vested in the hands of a pro-democracy leader. Deserved light needs to be shed on some troubling historical events of the era to chart the future course. Currently, the situation is becoming practically beyond our ken of analysis without the ventilation of the Enahoro perspectives. Therefore, we need to remedy the pre-existing condition that has become bereft of the essential gravitas. This we can do if we magnify expected impacts through an Anthony Enahoro Foundation.

Moreover, there is an ongoing battle for the soul of our country. In comparable situations, Chief Anthony Enahoro would not have kept quiet or stood aloof. He would either say something or lead others to organize and jointly chart a way out of the debilitating political and economic crises. Consequently, we need to look forward to one day when we will have the ability and resources to manage the intellectual heritage that Chief Anthony Eronsele Enahoro bequeathed to us to intervene in national discourse and tackle disturbing events.

The real possibility for scholars to engage Chief Enahoro and his peerless candour would leverage his can-do spirit and sparkling brilliance for the service of our country. Hopefully, we can even debate with Chief Anthony Eronsele Enahoro like Ali Mazrui did with Christopher Okigbo from the other side of the ethereal divide and do so in robust brilliance and unambiguous metaphor.

Conclusion

I will end this discourse in an untypical manner. It is important to extend our eternal gratitude to the High Commission of Canada and the High Commissioner in Nigeria in the mid-1990s, Mr Gerard Olsen, for rescuing Chief Anthony Enahoro from the jaws of death through assassination by agents of the Nigerian state. It was the Canadian High Commission not the United States Embassy as popular in street talks that ferried Chief Enahoro out of Nigeria and into exile during the pro-democracy struggle. The author of this book may not have recorded this external intervention to preserve the life of Chief Anthony Enahoro but Nigerians owe Canada deep appreciation.

We also thank Mr Eubaldus Enahoro who rose to a logical height befitting of the Enahoros of Onewa-Uromi, to fill a yawning gap in the life and work of Chief Anthony Enahoro. But this is just the beginning. And we should be grateful to the Uromi People’s Movement for the efforts to return the inimitable Chief Anthony Eronsele Enahoro to the front seat of national reckoning. Chief Anthony Enahoro’s voice resounds loud and clear in this book and in Nigeria, at large! His presence is manifest as a sine qua non, an ineluctable quality necessary in any vibrant national discourse. And it is the right time to mend awkward ways and leverage his wisdom for true service to our country.

Finally, I have the pleasure of commending this book, Chief Tony Enahoro: An Icon of Leadership, to students and practitioners of Nigerian politics and scholars of our history. All the leaders of our society, political, institutional or sociocultural, everybody interested in the foundation and future of our country, will derive practical benefits from reading this book.

Congratulations, Compatriots. And thank you for listening to this rather lengthy review and appertaining analyses.

Dr Onoho’Omhen Ebhohimhen teaches Political Economy of Development at Ave Maria University, Piyanko-Karshi, on the outskirts of Abuja, FCT.